Abu Simbel is a double triumph of human ingenuity, technology, and will. (To reach it, we hopped a short flight from Aswan, arriving at the site around 8:30 in the morning.)

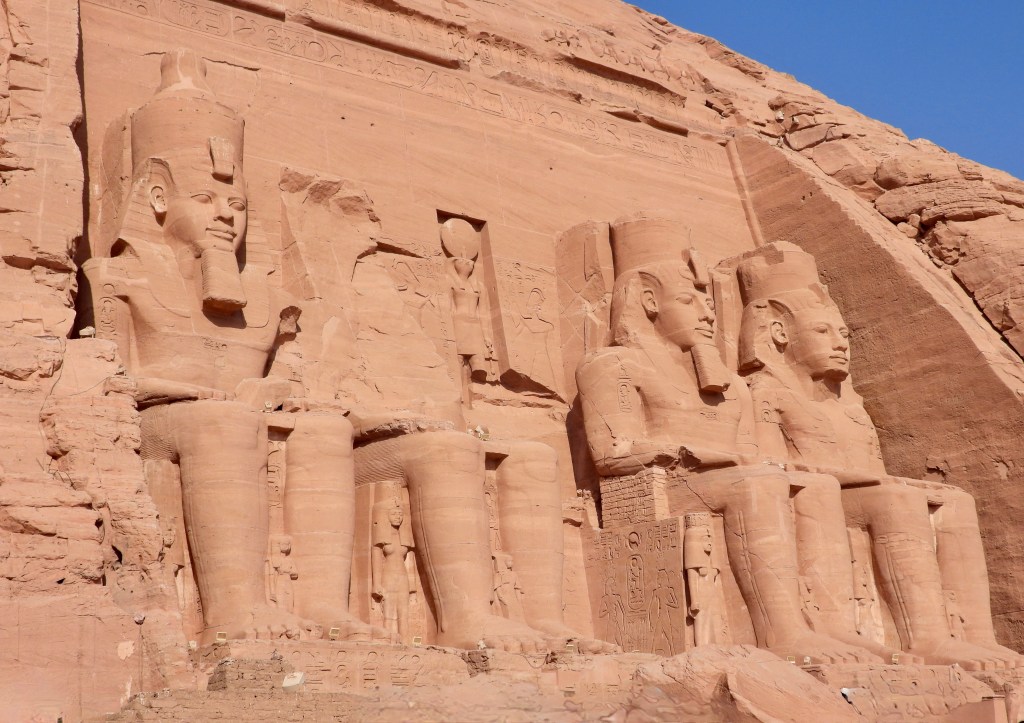

The first triumph occurred in the 13th century BCE, with construction of two glorious paeans to Egyptian power, the Grand Temple and the Small Temple. Ramesses II, one of the greatest Egyptian pharaohs, wanted to send a message to the Nubians, who were a big source of gold and other trade goods: don’t mess with us, and in fact, it wouldn’t hurt you to join us.

To this end, Ramesses constructed temples demonstrating Egypt’s might, with the mightiest of all being the Grand Temple (dedicated to the deified Ramesses as well as the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah), flanked by the Small Temple (dedicated to his chief wife, Nefertari, and the goddess Hathor).

The massive temples, carved into a mountainside, took workers only twenty years to complete. (I’ve had minor home improvement projects that seem to have taken longer, but then again, I don’t think any of my contractors regarded me as divine.)

The entrance to the Great Temple is guarded by four 20-meter-high sculptures of Ramesses sitting on a throne, with Nefertari, his mother, and eight of his many children at his feet.

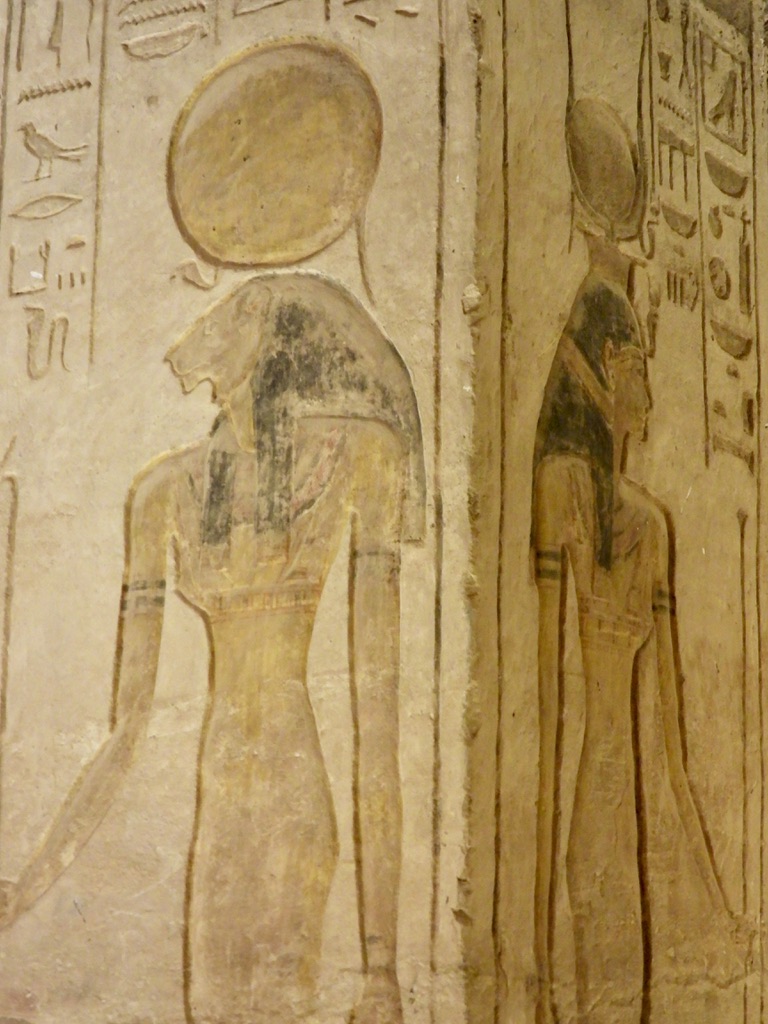

Inside, large statues of Ramesses/Osiris overlook bas-reliefs depicting Ramesses’ military engagements, chiefly the standoff battle of Kadesh, which ended in a truce when Ramesses married a Hittite princess. Pillars in each room are painted with offerings to the gods.

It’s a remarkable artistic achievement, further enhanced by the temple’s orientation in relation to the sun. Specifically, on October 22 and February 22 (two months either side of the winter solstice), the sun’s rays penetrate to the back wall of the temple, illuminating statues of Ramesses and his fellow gods. Some people have speculated that these two dates were Ramesses’s birthday and coronation day, but there’s no supporting evidence.

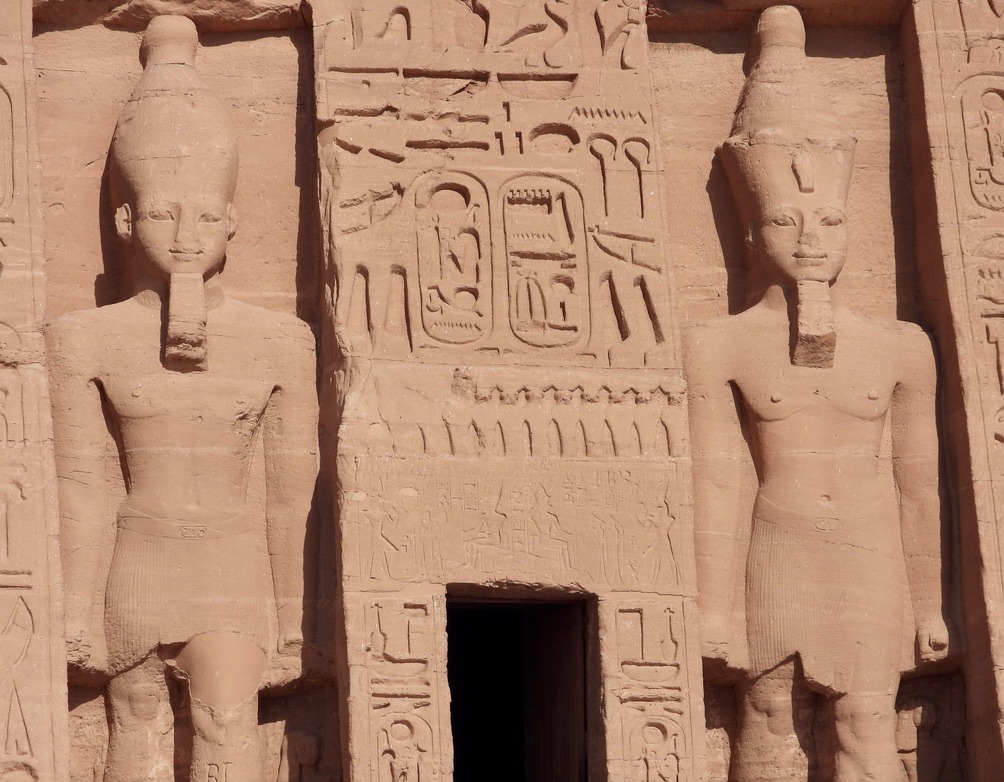

A short distance away, the entrance to the Small Temple is flanked by statues of Ramesses and Nefertari. Inside, columns show Nefertari playing an instrument in the company of various gods and goddesses. Other decorations celebrate Ramesses’s military activities and depict Ramesses and Nefertari making offerings to Hothar.

The temples are spectacular; their majesty isn’t even marred by the hundreds of tourists flitting around mimicking the artwork and taking selfies. Nonetheless, my curmudgeonly self found the frantic pursuit of silly selfies both disrespectful and disappointing. I don’t understand how people can travel all the way to a remote part of Egypt without taking time to contemplate the beauty and human achievement of these ancient wonders.

I’ll get down off my high camel now and move on.

Alas, the inexorable – and literal – sands of time eventually had their say, largely burying the temples for many centuries. In fact, no European knew of their existence until 1813, when a Swiss researcher, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, noticed portions of the four statues flanking the entrance to the Grand Temple: “The entire head, and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues are yet above the surface; of the one next to it scarcely any part is visible, the head being broken off, and the body covered with sand to above the shoulders; of the other two, the bonnets only appear.”

Four years later an Italian explorer, Giovanni Belzoni, managed to clear away enough sand to gain entrance into the Grand Temple. (The sand wasn’t entirely removed until 1910.)

Fast forward to the 1960s. As I mentioned in yesterday’s post, construction of the Aswan Dam threatened to inundate Abu Simbel under several hundred feet of water. After rejecting several impractical schemes to save the temples, engineers figured out how to safely cut the temples into blocks and reassemble them at their current site on higher ground nearby. (Funding came from UNESCO, Egypt, and the United States.)

To replicate accurately the original look of the site, the final touch in the relocation was to rebuild a mountain behind the temples, immediately calling to my mind (if no one else’s) Donovan’s hit: “first there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is.”

The project was completed by the summer of 1968, and one of the great triumphs of human ingenuity, design, and will was saved by another one 33 centuries later.

After flying back to Aswan and eating lunch, we returned to the hotel around two in the afternoon. Amr, our guide, once again went above and beyond by arranging an optional boat ride around Elephantine Island. The short cruise took us past sites important in Agatha Christie’s “Death on the Nile,” the hilltop Mausoleum of the Aga Khan, and several slice-of-life scenes of Aswan residents going about their business.

After a remarkable, inspirational, exhausting day, I retired early. Our next three days will be spent cruising the Nile up to Luxor. Salam for now.

What a full, inspiring day! Abu Simbel really is spectacular, for all of the reasons you note. I expect you’ll be equally awed by what’s ahead in Luxor.

I’m sure I will. We’re going to do a three day cruise up the Nile to get there.