According to the Happy Planet Index, Vanuatu took first prize in 2024 as the “happiest place on earth.” Granted, it’s an inherently subjective calculation, using people’s expressed satisfaction, average longevity, and ecological footprint to produce a score representing how much happiness “bang” a population gets from its ecological “buck.” Even so, based on my brief visit, the rating sounds about right given the inputs – largely because many people hew to traditional, low-stress, sustainable lifestyles, which I’ll talk more about in a few paragraphs.

In the morning, my brother and I walked into Port Vila, the nation’s capital and main population center. Port Vila is 3 km from where cruise ships dock. It’s an easy walk, although for most of the way there are no sidewalks Alternatively, there are taxis and water taxis that will bring you to town for $5 AUD or $ 5 USD – given the exchange rate between Australian and American dollars, it’s worth carrying some Australian currency.

Being Sunday, most attractions, including the produce market and the well-regarded Vanuatu Cultural Centre, were closed. Shops and the handicraft market were open, but only because our cruise ship was in town.

The city is compact, colorful, and friendly. Nearly everyone we passed said “good morning” and “how are you,” not reflexively but with sincerity. Women in the handicraft market, rather than pressuring us to purchasing something, offered warm smiles and a genuine interest in where we came from.

In the city, almost all the women and children, and some of the men, wear vibrantly colored and patterend clothing. To me, this brightness further enhances the city’s beautiful setting on the shore of a pristine lagoon. (Water sports enthusiasts take note: there are myriad opportunities in town to hire a boat, rent scuba or snorkel equipment, or take a glass-bottomed boat tour. One attraction for those so inclined is the world’s only underwater post office, reachable by boat and located three meters below the surface.)

There’s a lovely, well-maintained park running for a few blocks along the water. Sea urchins and small fish are visible from the seawall, and crabs scurry under steps or into the water whenever they encounter a shadow.

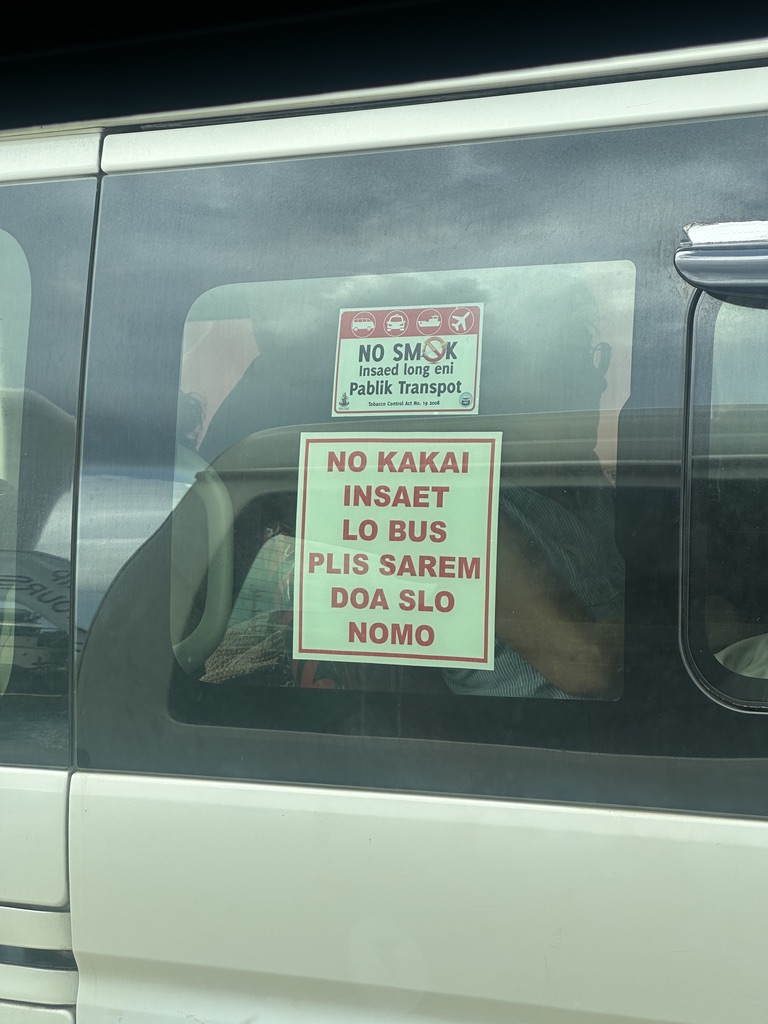

Vanuatu has more languages per capita than any other country, with over one hundred indigenous tongues. English and French are taught in schools, but Bislama, a creole language, is spoken by almost everyone and is often found on signs.

Ten minutes outside Port Vila, life is nearly unchanged from the centuries before Europeans arrived, as my brother and I found out during an afternoon tour of the Ekasup Cultural Village. At first I thought this was merely an in situ museum designed to show how life used to be – an erroneous notion bolstered by the “warriors” hiding in the jungle who ”threatened” us as we approached the village, creating a rather cheesy first impression.

In fact, though, Ekasup has been a village for over two centuries. Its 500 residents hunt, fish, manufacture necessities, live, and observe traditions as their ancestors have since pre-contact times.

Their woven attire and headdresses are not costumes donned for visitors; they are their everyday clothing, variations on which denote status. For example, chicken feather worn in a headband indicate that someone is a pig farmer; the colors of the feather match the colors of their pigs. Such villages pervade the islands of Vanuatu, with 75 percent of Ni-Vanuatu living in rural settings; the difference is the Ekasup has been made into an exemplar for tourists.

The village residents have made some concessions to “modern” mores: they used to wear far less and they have replaced traditional polytheism with various sects of Christianity. In other respects, though, life is “same as it ever was,” to quote the Talking Heads.

The village elder who conducted our tour – his English is excellent, the result of a 7thgrade education and years of talking to tourists – explained that his people still fish with bow and arrow, spears, native vines whose juice removes oxygen from the water, stunning the fish, and sticky nets made of rolled spider webs. He also showed how they build traps baited with coconut to catch wild boar and chickens.

Next he explained how jungle plants are used for medicinal purposes. For example, an iron-rich brew made from coleus leaves is given to pregnant women, and the stem of the Madonna lily dispenses drops of coconut milk to help a newborn breathe.

Gender roles are divided along traditional lines, and grandparents arrange marriages for their grandchildren. The entire 500-person village is considered a family, producing a cohesive unit with minimal friction. Our guide couldn’t understand why anyone would live in a city instead of the low-stress, idyllic life the villagers enjoy, with everything they need available from the ocean or the surrounding jungle.

Our visit to the village closed with a performance featuring traditional instruments (along with guitars) and young men performing militaristic dances.

The visit to the village reminded me that there are many ways of approaching happiness. A low-stress, friction-free lifestyle that leaves the environment largely undisturbed sounds nice on paper and helps Vanuatu score highly on the Happy Planet Index. But the rigid social structure and day-to-day sameness would drive me crazy. We all have to look for happiness in our own way, while respecting others who have different, but equally effective, paths to the same end.

I’ll close on that philosophical note. Next up, after two sea days: Brisbane, Australia.