Our visit to this half-beautiful city began with a terrific on-board lecture from a Serbian historian who condensed 2000 years of invasions, uprisings, massacres, unifications, divisions, reunifications, and redivisions into a single hour. The bottom line: Belgrade has been invaded, prized, occupied, destroyed, and rebuilt by every major empire since the Dacians, and Serbians have been on the receiving and giving end of some truly barbaric behavior.

Today’s Belgrade is a tale of two cities. East of the Sava River (a tributary of the Danube), the city is cosmopolitan and bustling. Stately buildings, lush parks, a fortress dating back nearly 2500 years, a business district called (proudly by some, disparagingly by others) the Serbian Dubai, St. Michael’s Cathedral, a royal palace compound, and pedestrian promenades lined with cafes and designer clothing stores lend a sophisticated central European air to the area.

Across the river lies “New Belgrade,” much of which is shabby and besmirched by communist-era apartment blocks and the seedy remains of the once-spectacular Hotel Jugoslavia. Appearances, though, don’t tell the entire story. Our guides on a bike tour this morning said New Belgrade attracts young families, and the monolithic apartment blocks, for many, have taken on an air of retro chic. There’s also a park along the riverfront (the Danube in this case) teeming with bikers, rollerbladers, joggers, and kids and lined with floating restaurants and nightclubs. A few blocks away from the river, there’s a district of coffee houses, bars, and restaurants.

Biking through New Belgrade on a tour this morning, we stopped first in front of a small, out-of-the-way memorial to the 40,000 Jews, Serbs, and Roma killed at that site by the Gestapo in World War II. The memorial is fairly recent: during Tito’s reign there was no desire to acknowledge this loss due to a fear of stoking ethnic tensions and undermining the fragile Yugoslav alliance. Now, though (with ethnic and religious tensions running high), there are plans to convert an adjacent area currently occupied largely by Roma into an extensive memorial. (No word on what will happen to the Roma.)

As the temperature hit 90, I returned to the ship for a change of shirt, a gallon or so of water and ice tea, and a light lunch. Then I headed off on my own into the old city, which as noted above is far more attractive and interesting than the new part of town.

Later in the afternoon, Talija Art Company, whose musicians (two accordions, a violinist, and a drummer) and dancers treated us to a high-energy, amazingly athletic performance of Serbian folk dances. It left me exhilarated and with knees, back, and hips vicariously in a state of shock.

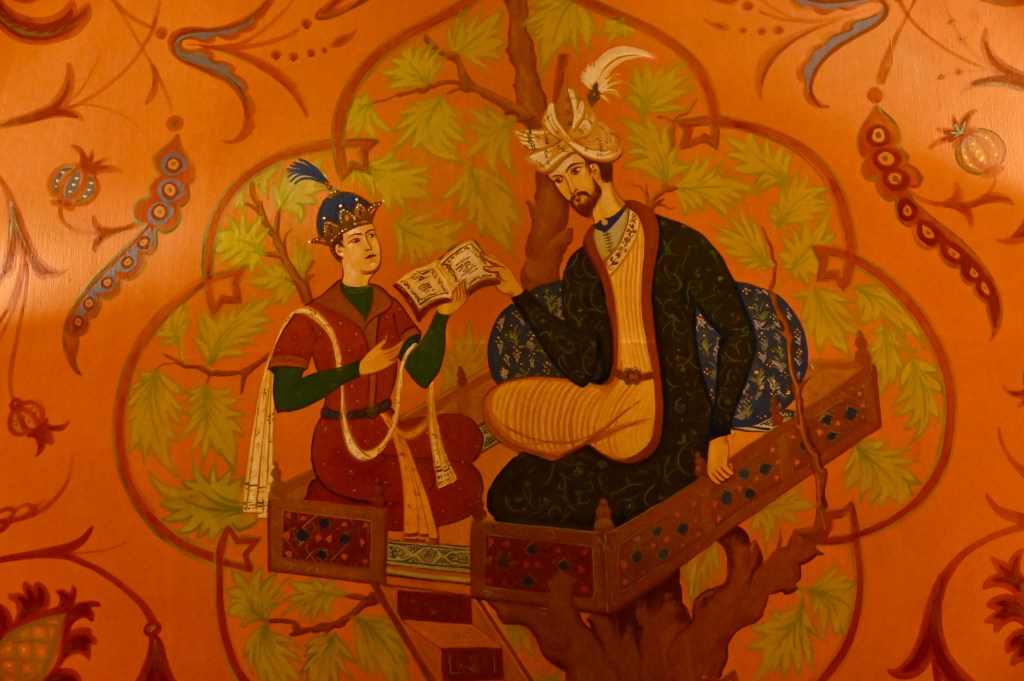

For dinner, Tauck took us to the Royal Palace for a tour, and then to the nearby White Palace to eat. The Royal Palace is stuffed with antiques, lush carpets, ornate ceilings, a colorful chapel, and rooms with decor depicting the story of The Firebird (a traditional Russian tale best known from Stravinsky’s ballet).

It’s still home to the son of Romania’s last king, Crown Prince Alexander, and his wife, Princess Katherine. Like almost every other royal in Europe, Alexander is a direct descendant of England’s Queen Victoria. (Alas, they did not stop by to give us a royal wave.) Other than the entry hall and a dining room, we didn’t see much of the White Palace.

Thus ends our trip to Serbia. I found Belgrade to be both a testament to resilience and a poster child for the high cost of religious and ethnic tensions and the durably pernicious effects of communism. Serbia is a beautiful country, and the Serbians I met were lovely people. Unfortunately, all of the former Yugoslavia seethes with long-held resentments. Perhaps once Serbia and other ex-Yugoslav states become EU members (if that happens) then a more peaceful equilibrium will be reached.